What’s the best compliment you can give an author?

I think I found the answer, and it was from a podcast. I recently finished Tim Ferris’ interview with Morgan Housel, author of The Psychology of Money. Tim opened the discussion with the following:

I was extremely impressed with how many, not just anecdotes, but reframes in the book caught me off guard or were totally unknown to me or were hiding in plain sight…

That really resonated with me. Yes, good writing needs to be clear, crisp, and informative, but there needs to be more. It must capture your attention, and surprise you. That’s when we learn the most.

The most insightful writers take seemingly obvious observations and turn them into profound revelations.

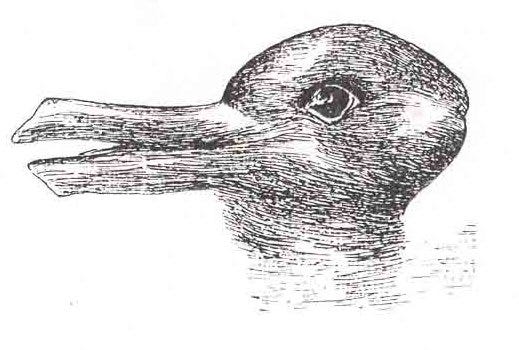

When Tim said that, this picture came to mind:

I first saw the duck (and then the rabbit) in elementary school, and my nine-year-old mind was blown.

That’s what these writers do. They see something we’ve been looking at every day, and they show us what we've never noticed, or at least what we never consciously recognized. And I use that word deliberately.

My high school English teacher emphasized the importance of the word recognition. Etymologically, it comes from the Latin verb recognoscere: ‘to know again, recall to mind’. It quite literally means that we’re seeing something again, becoming re-aware of its importance. This was a random point mentioned one day while we were working our way through The Odyssey, and it's totally changed how I think about that word.

I mention all of this because there’s another writer who has changed my view of the world, to the point where I’m now recognizing all sorts of second images.

The Storytelling Animal

Last week I mentioned a book called The Storytelling Animal. It's really thought provoking — this early quote gives a glimpse:

Tens of thousands of years ago, when the human mind was young and our numbers were few, we were telling one another stories.

And now, tens of thousands of years later, when our species teems across the globe, most of us still hew strongly to myths about the origins of things, and we still thrill to an astonishing multitude of fictions on pages, on stages, and on screens—murder stories, sex stories, war stories, conspiracy stories, true stories and false…

Story is for a human as water is for a fish — all-encompassing and not quite palpable.

— Jonathan Gottschall, The Storytelling Animal: How Stories Make Us Human

Jonathan mentions that stories and dreams (which as I mentioned last week, are stories themselves), are the air we breathe.1

Stories are a good place to start. After all, every society, and everybody tells stories. One of Yuval Harari’s more interesting conjectures in Sapiens is that stories are how humans escape Dunbar’s Number. The ability to believe in shared myths like corporations and nations was what led to humans to cooperate beyond nature’s original limits.

Ever since the Cognitive Revolution, Sapiens have been living in a dual reality. On the one hand, the objective reality of rivers, trees and lions; and on the other hand, the imagined reality of gods, nations and corporations...

...As time went by, the imagined reality became ever more powerful, so that today the very survival of rivers, trees and lions depends on the grace of imagined entities such as the United States and Google.

— Yuval Noah Harari, Sapiens

I’ve talked about stories a lot on Embers. They make reading more engaging, because they’re how our minds work. Stories are how we understand the world. And The Storytelling Animal, itself suffuse with stories, is a comprehensive analysis about why that’s the case.

Well, that got me thinking about what else we're swimming in.

There are other things, outside the scope of Jonathan’s book, that are floating in the water with us. And I’m starting to recognize them. But before I dive in, it’s worth asking why this really matters.

Can We Get Out of the Water?

You may wonder why it’s necessary to spend so much time thinking about the water we’re swimming in. After all, we can’t really get out, right?

I’m not so sure. And here’s a story to help explain why:

One of my favorite yoga instructors has been teaching for 25 years, which is wild because that’s how long I’ve been alive.

The reason I know this is because I went to an “introduction to yoga” class he had a few weeks ago, and he couldn’t understand why I, one of the regulars for his intermediate and advanced classes, was showing up to learn what the 4 basic yoga poses were.

While that class wasn’t physically challenging, it was the most important one I’ve taken, because it gave me a new way of seeing yoga. One other student and I spent an hour with someone who’s been teaching for a quarter of a century, and we got to ask all sorts of questions that normally we would never get the chance to.

It completely transformed yoga for me, because I now have a deep understanding and appreciation of the core elements of a yoga class.

When you spend enough time doing something, you start seeing things in a different light. Grand Master chess players don’t see individual pieces on a board, they see chunks of pieces together as individual elements. Tom Brady and LeBron James see different football and basketball games than we do.

I’ve seen this firsthand with sports, and now I’m seeing it again in both my investing career and my personal learning endeavors.

When you know the details behind why something is, you gain a deeper understanding and appreciation of what you’re interacting with, and that in turn helps you be more effective, more adaptive, and more creative.

Intimately interacting with the basal elements of something doesn’t diminish its value, it enhances it. Johnathan speaks to this as well:

The idea that stories slavishly obey deep structural patterns seems at first vaguely depressing. But it shouldn’t be. Think of the human face. The fact that all faces are very much alike doesn’t make the face boring or mean that particular faces can’t startle us with their beauty or distinctiveness.

As William James once wrote, “There is very little difference between one man and another; but what little there is, is very important.”

The same is true of stories.

— Jonathan Gottschall, The Storytelling Animal: How Stories Make Us Human

We might not be able to get out of the water, but we can become more masterful with it.

It’s So Overt, It’s Covert

Last year, I wrote a piece called New Beginnings, which examined how fresh starts, unencumbered by existing constraints (Inherited Assumptions), can lead to powerful innovations and advancements.

I think much of that piece still rings true today, but the relevant excerpt lies in the opening:

Inherited Assumptions

One of the exciting ideas you can’t unsee is that everyone around you exists because someone decided to make it so. Humans have collectively built an ever expanding civilization — this is something Tim Urban talks about on Wait But Why.

Once you realize this, you also notice that we inherit decisions made in the past. These decisions were made with assumptions from their time frame, which means that the world we live in is a lagging index of what people think the world looks like.

The idea that the world we’ve inherited is the direct descendant of decisions people made in the past is on its face, obvious, but it contains a powerful message. What we do with our lives matters — our decisions carry weight. And while our actions may not be easily tied to today’s and tomorrow’s State of Affairs, they are intrinsically linked.

In a sense, this is the very essence of the water we’re swimming in. Everything is downstream of our decisions. The stories we share, the things we build, are all acts performed by us, our ancestors, and our descendants.

I’m a big believer in how empowering this is. To an extent, much of what I write about in Embers stems from this very idea. There’s value in examining the obvious, naming it, and actually spending time thinking about it. The Storytelling Animal gave me a name for this exercise: looking at what we’re swimming in. When you take time doing this, you see how it’s a wonder to be here, the mystery never leaves you.

I struggled writing this because there are so many ways to take this piece: I could examine how music pervades all cultures, and how dances and feasts are featured prominently in any place or time period.

Or more notably, I could spend time talking about the magic of our technologies. Our smartphones, our headphones, and so much more. We take for granted that we can conjure any lyrical tune directly to our ears, and yet that is such a special thing to do.

Or consider our ability to call or message people across the world. We see happy stories, breakup texts, or disheartening details about wars. We are looking at symbols on a screen, sent by someone else, and not only can we understand them, but they can induce us to lust, laughter, and heartbreak.

We don’t think about the mechanics behind this because it’s just natural, but that’s what’s so mesmerizing about it. It literally is part of the air we breathe.

Appreciating the magic of this all is surely one of the best ways to live life. And in doing so, you can concoct these elaborate, rich stories. As noted in Becoming a Mental Architect, we get to create the stories we tell ourselves about our self.

Being a mental architect isn’t about reaching peak efficiency or optimizing everything — it’s about making the most of this fleeting journey. At the end of the day, if you can create a rich existence in your mind, then you’ll experience life in that very manner. Sometimes bad things happen and a thorn gets stuck in our side — the proverbial song stuck in the head — but you can create your own mental environment, and actually influence your brain’s tuning fork. New possibilities emerge once that happens, and in turn you begin emitting a new frequency, one that ripples outwards to others.

Sheepishly, I’d suggest that the Metaverse has already existed for hundreds of thousands of years. That’s what stories are, they’re these virtual worlds we immerse ourselves in.

And all of these things, whether they be stories, spaceships, or smartphones, share the same quality: we created them. All we had to do is take some time to recognize it.

It’s the water we’re swimming in.

John Watson: (Referring to Holmes’ outfit). Isn’t it a bit conspicuous?

Sherlock Holmes: It’s so overt, it’s covert.

One of the key quotes from Becoming Limitless:

What are dreams, but stories our brains make up? And what are books, but stories other brains have made up? The commonality between both is that they can change us, and we don’t even need to recognize it

Interestingly, this is one of those examples of how writing is mental alchemy. This idea came to mind as I was working on the piece. It fumbled its way out onto the page before I even registered what it meant.