The news was horrible this week. Then again, it’s been pretty horrible in all sorts of ways for the past few years now.

Stuff like this often makes us long for the Good Old Days — when things weren’t as complicated, crazy, or catastrophic.

But when were they? Did they ever really exist?

I’ve been really interested in this notion of reminiscing on the Good Old Days for some time now. It seems like something that only applies to us now, but as I’ve read more and more, I’ve realized that we have always felt like this.

"We seem perennially tempted to contrast our tawdry todays with past golden ages. We apparently share this nostalgic predilection with the rest of humanity." — Robert D. Putnam, Bowling Alone

If this has always been true, then the chief question becomes: why?

I may recall an answer.

Remembering Memories

When you ask yourself what the best time of your life was, what do you think of?

Is it today? Or is it in the past?

Chances are, your answer falls upon your childhood, when you were young, naïve, and possibly a bit oblivious.

There are a few reasons: we don’t have many responsibilities as a child. If you were lucky, these are the years when you have no financial, work, or marital commitments. You were left free to be.

I talked about one of the other reasons a bit last week via Type II Fun:

There’s a biological reason why this happens. Our brains do a great job of clouding our recollection of previous pains we’ve suffered. There are probably a lot of valid reasons — but probably the most important is that this is what wills the human race forward. If we remembered all the toils in terrific detail, we wouldn’t want to do it again…

People can’t really remember pain. This is a good thing, since not many women would choose to have more than one child if they did. People will even feel nostalgic about appalling experiences like war, if they happened at certain times of their life, like say when they were under 30.

Now these are broad brush strokes, so this isn’t true of everyone, but generally speaking, we don’t remember much of the bad stuff. And this has been proven psychologically, as Daniel Kahneman outlines in Thinking Fast and Slow.

So we idolize the good stuff, diminish the bad, and we’re left with this idyllic picture of the past. And it’s often colored by our limited understanding of the world from our childhood innocence. And this has happened over and over throughout the ages. It’s another great example of how History Rhymes.

Here’s an excerpt from one of my favorite WSJ articles from last year:

People have been longing for the good old days at least since the invention of writing in ancient Mesopotamia, 5,000 years ago. Archaeologists have discovered Sumerian cuneiform tablets which complain that family life isn’t what it used to be. One tablet frets about “the son who spoke hatefully to his mother, the younger brother who defied his older brother, who talked back to the father.”

Another, almost 4,000 years old, contains a nostalgic poem: “Once upon a time, there was no snake, there was no scorpion… The whole world, the people in unison… To [the god] Enlil in one tongue gave praise.”

— Why We Can’t Stop Longing for the Good Old Days

It’s important to appreciate and understand this, because it’s easy to get lost in the past.

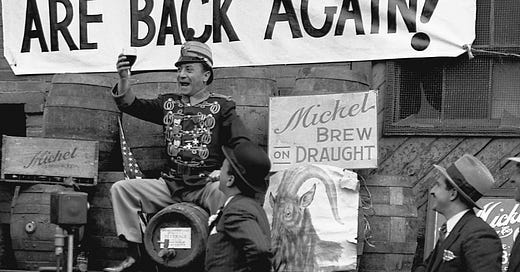

We overly romanticize the good at our own peril — I’m reminded of this scene from Midnight in Paris in particular:

It seems that we always are susceptible to a bit of “the grass is always greener somewhere else” mentality. And when that’s combined with nostalgia, and youthful ignorance, we’re left yearning for something we can never have: a return to The Way Things Were.

This scene shows us that no matter what, we have to live in the present. Being born in a different time, in a “greater” era, would not bring eternal happiness — we will always be unsatisfied with what we have. Goalposts move. Comforts change. Life always has some rain. We have to remember this, especially when bad things happen. Because bad things always happen, sometimes we just forget to remember them.

I recall a recent tweet by Balaji, from the beginning of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. He bemoaned what was happening, and shared this simple thought:

But was it?

Off the top of my head, I can think of Ruby Ridge, the Waco Texas standoff, the Oklahoma City bombing, the tech bubble crash, and 9/11.

I don’t even know if these are the most important events from that era, but the point is that even then bad things still happened. And this doesn’t cover all the good things that have happened since then (a good example is Obergefell v. Hodges).

Regardless of your political leanings, I think we can all agree that if you asked someone who wasn’t white if they were better off in the 90s, it’s fairly safe to presume they’d say “no”.

This is an observation, rather than a political statement. And one that illustrates that we have progressed as a society from those seeming “idyllic times”.

So maybe our memories are fallible. They’re not necessarily wrong, though more research is showing us that that is increasingly possible, but rather they’re incomplete — limited by our perception of the world, and then biased by nostalgia.

And yet even if this is all true, what about more objective evaluations? There are reasons why certain time periods were called the Golden Ages while others were known as the Dark Ages. So where do those fit in?

Golden Ages

People have always been longing for the good old days. But when we actually start looking at them, it’s hard to find them.

Returning back to that same WSJ article:

In fact, many in the 1950s thought that the good old days were to be found a generation earlier, in the 1920s. But in the 1920s, the pioneering child psychologist John Watson warned that because of increasing divorce rates, the American family would soon cease to exist. Many people at the time idealized the Victorian era, when families were strong and children respected their elders. But in the late 19th century, Americans were worried that the unnatural pace of life brought on by railroads and telegraphs had given rise to a new disease, neurasthenia, which could express itself in anxiety, headaches, insomnia, back pain, constipation, impotence and chronic diarrhea.

There are countless other examples.

Progress solves many of society’s problems, but once these issues fade away, then they drift out of our memories. And we know that we’re especially good at forgetting the bad, and remembering the good. Maybe this is why we long for the idyllic aspects of yesterday, when forgetting that today we’ve solved many of yesterday’s problems.

The best way to answer when the Good Old Days were is to rephrase the question: if you could pick any time period to live in, what would you choose?

It’s a multi-tiered question — there’s the personal component, of course, which as I discussed above is usually fixated on our childhoods. But there is also the broader, macro side to the question: what time period specifically would you choose?

At first many people are quick to point to the past, but when you dive deeper, you realize that the world wasn’t all that great.

Interestingly, every religion has some ornate depiction of the Golden Ages — the Greeks had theirs, Judaism and Christianity had Eden. I find it another example of how Stories Rhyme, just as history does. But it also illustrates a deeper aspect of what makes us human. We innately reminisce about the Good Old Golden Ages. And when I think about What’s Changed, and past Golden Ages, I think back to Greek Mythology, specifically a certain section from Mythos:

"Perhaps we only imagined these first days of beautiful simplicity and universal kindness so that we could have a high point of paradisal sublimity against which to judge the low, degraded times that came after. The later Greeks certainly believed that the Golden Age had truly existed. It was ever present in their thinking and poetry and gave them a dream of perfection to aspire to, a vision more concrete and realized than our own vague ideas of early man grunting in caves. Platonic ideals and perfect forms were perhaps the intellectual expression of that wistful race memory." — Stephen Fry, Mythos

Whether or not you believe that the Good Old Days existed, I think it’s important to see them as a North Star. Something to aspire to, as Stephen says.

Aspiration and Ambition really matter, and as I look around the world today, I see plenty of things to be upset about. But I also recognize that it’s never been easier to see bad things thanks to social media and globalization. Technology has Changed the Calculus, and now we see everything: both good and bad. And much of the media amplifies what’s bad, because they know that it pulls us in. It elicits fierce reactions.

I’ve said this many times in Embers, but Looking in the Dark is really important. You have to see what’s wrong with the world in order to know what must be fixed. For me, the quote above acts as a mindset, teaching us what to do when we find ourselves thinking about how yesterday was so much better than today.

Objectively speaking there are definitely days that are better than others. But equivocating entire eras to today is a mistake. Because the world is often much more complicated than it seems. And instead, we would be better off figuring out what it is we really want to be better, and set out to fix them.

Progress is never guaranteed. And if you need a good example, take a look at Argentina. It was heralded as a true beacon of hope for developing countries, and then things took a turn for the worse.

These tweets illustrate that bad things can and do happen. People are the only reason why we have the world we live in today. The Good Old Days we all crave were created by people like us, and that brings a responsibility to do the same for the future.

Goodbye’s

Thursday was my last day at MetLife, the place where I spent the last three years learning, investing, and becoming better. It is always hard saying goodbye, especially when it can often be so unceremonious (as I discussed in The Fuel of Failure). Fortunately my last day (and week) was more planned out, but it was still hard.

One of the ways I’ve come to counteract conclusions to current life chapters has been to write — specifically about the life lessons, takeaways, and memories that I will take with me. I won’t regale you with all of that here, but I do want to share one story.

When I decided to share a piece of writing every week this year, I was a little scared. I know some of my coworkers read what I write, and with that knowledge comes a vulnerability and even shyness. But most of the pieces weren’t that vulnerable, so these feelings weren’t that hard to overcome.

But when I got ready to publish What I’m Here For, I became nervous. It is a pretty ridiculous thing to write, and it’s not a part of me I freely share. I didn’t know how people I respected would react to it. But I soon found out because one of my coworkers emailed me right after they read it.

I remember sitting at my desk in my apartment nervously clicking on the email, not knowing what it would say. This coworker and I had never talked about the types of things I discuss in that piece. But reading their response to the piece was really impactful; it was effusively supportive, and I was so grateful that they took the time to write it.

This ended up being really cathartic for me, and reaffirmed that it’s worth being vulnerable and sharing what matters to you.

Funny enough, when I wrote about my biggest personal failure weeks later, it wasn’t intimidating at all, because I already had taken that leap, and realized that people will be there to support you.

There’s that scene from the season finale of the Office TV series, where Andy says something pretty profound:

“I wish there was a way to know you’re in the good old days, before you’ve actually left them.”

As discussed above, there are neurological reasons why the Good Old Days are always behind us, but sometimes there’s another, simpler explanation: sometimes the old days really were that good.

There’s something to be said about knowing when something good is coming to a close — when that’s the case, goodbye’s are especially hard.

In my case, it feels bittersweet to move forward onto new things. As I’ll expound in the coming weeks, I’m very excited for what’s next, but that doesn’t change how I feel about leaving.

Part of living is having people come in and out of your life. Sometimes they drift in and out, other times they’re torn away too early. But this is one of the reasons why I wrote Defying Death. Even if certain people are not presently in your life, that does not mean they’re fully gone. They’re still with you, and your memories of them are a very real, living thing.

So smile and look back at all the great Good Old Days, and use that to inform how you live today. Because having good old days doesn’t preclude you from making new ones.

My time with my colleagues at MetLife firmly falls into the Good Old Days. Their presence in my life was a true present, and I know that regardless of how often we are able to connect in the coming months and years, I’m all the better because of them. And that’s the best thing you could ask for.

We’re living in the Good Old Days right now, and all we have to do is keep enjoying them.